Subscribe

Normally we publish only once per week, but we wanted to get this highly topical episode

live as quickly as possible. Steven chats with Ed Parsons, Google's Geospatial Technologist, about Google's recently released

COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports,

Relevant links:

About the podcast

On the Geomob podcast every week we discuss themes from the geo industry, interview Geomob speakers, and provide regular updates about our own projects.

Popular podcast topics:

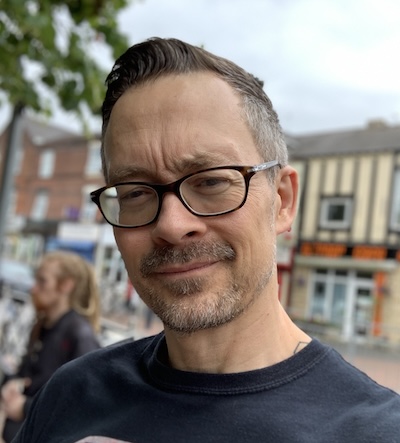

The Geomob podcast is hosted by:

Autogenerated Transcript:

Ed 00:01 Welcome to the geomob podcast where we discuss geoinnovation in any and all forms it for fun or profit.

Steven 00:11 Good evening, the ceiling. I've got the great pleasure of talking to my good friend ed Parsons from Google. And so this evening we're going to be talking about Google's new community mobility report, but before we do, let me introduce that to you at Parsons is the geospatial technologist of Google, which is the most fantastic title that I think anybody working in the geo world has ever had. He's responsible for evangelizing Google's mission to organize the world's information and he's also a member of the board of directors of the open geospatial consortium. What you and I know as the OGC, and he was cochair of the W3C, OTC spatial data on the web working group. To add to that, he's a visiting professor at the, at university college in London and he's based at Google's office in London and anywhere else he says where he can plug in his laptop this evening. His laptop is plugged in in his home in West London and we're talking across the internet and with me and North London. So good evening, ed. Thanks very much for joining us.

Ed P. 01:23 Good evening, Stephen. It's a pleasure to be a one of the members of the podcast. I've been an avid listener for your, your relatively few podcasts so far, but as part of my evening walk, my exercise, I've, I've been, uh, an intense listener to yourself, an artist.

Steven 01:39 That's great to hear. Thank you. So how's it working for you being locked down in London rather than traveling the world on first-class airplanes all the time?

Ed P. 01:51 Yeah, no, the first class travel, you exaggerate. It was never first class travel. Well maybe once or twice I got upgraded perhaps. No. So yeah, that bit is clearly out of the window and that part of my job has, has changed enormously. But actually most of what I do hasn't changed that much. You know, I like many people at Google, he used to working remotely, you know, a kind of joke in my bio that my office is wherever my laptop is. And, and that that's pretty much the case where we're sort of set up to work in the cloud to work remotely. So you know, many of the kind of regular meetings I have, we carry on having, I've been reaching out to many people over the past couple of weeks talking about the apps they're trying to develop or working with various government organizations about, you know, day tracks and so on. So all of that has continued, uh, pretty much the same way that it used to. The, the only bit I'm I'm missing and I am missing it is, is not meeting people in the,

Steven 02:50 ah, yeah. Well that's going to come back. Hopefully you just mentioned something that interests me. I just talked about talking to government people about data and that have things changed particularly since the Corona virus or,

Ed P. 03:05 yeah, in some ways. I mean we've, we've very, you know, Google has always had this very strong focus on, on our users. So you, we try to carry on doing what we're doing because our users expect us to do. So. A lot of the focus has been on making sure you know, things like Google maps or you know, up to date and accurate representing the enormous change that's gone on over the past few weeks know around the world. So you know, a huge effort in terms of making sure that the opening hours of of shops and and places you might normally visit are updated and are accurate. And that's been a, you know, as you can imagine the huge task. Yeah. And, and kind of making some sort of intervention. So if you search for, you know, your local GP surgery or hospital, well we'll put up a warning dialogue box and say, well, you know, under the current circumstances you really shouldn't be planning on going to visit these places unless you have a good reason to do so. And, and just today we sort of focus now more on, on restaurants that provide takeaway services and making sure that they're, they're exposed through, through Google maps. And you know the big rationale there is is well where do you normally go for this information? Well you should be able to find the information there. You know, you were not keen on developing new channels or new ways of accessing this information because it's not what people are going to use. Not what.

Steven 04:28 So if I search for my local supermarket, I won't mention the brand, would you be able to tell me how long the queue is outside at the moment?

Ed P. 04:36 Not quite, but I know some people that might be able to do those as you would expect under under the circumstances there's a, there's a big sort of ecosystem and keen app developers are, are putting together some quite exciting apps. The crowdsource sort of information, we can tell you the opening hours and how they may have changed and we can give you some sense of how busy it is. But, but there are groups that are focused on, on those particular problems. Just saying, you know, under the current circumstances, how long is there a queue outside your, your local,

Steven 05:07 that would be very useful. Okay. So when you were talking about opening hours and stuff like that, I thought it made me think about some of the data that you're collecting cause you do collect data which says the busy hours in a place are between such and such and such and such don't you?

Ed P. 05:24 Yeah that was in many ways the, the starting point for the, the community mobility reports that we've launched. Yeah. As as a sense of, well we have some pretty good idea of how people are moving around the world. How can we make that information available to, to health agencies, to, to government planners to that they can get some sense of how social distancing strategies are working.

Steven 05:48 And so tell me a bit more about the mobility report. What do they comprise? How did you build them? So

Ed P. 05:55 the general idea is is that we think roughly a third of the world's population at this point in time is under some form of, of restriction in terms of how, how you can move about. And you know, you just watch the TV probably anywhere around the world. You'll see all sorts of decisions are being made with best efforts of government and various agencies, but, but not with a huge amount of data behind the scenes. You know, this has been, uh, up until this point, uh, a crisis has been quite poor in data but, but quite heavily reliant on models that require lots of data. So we have been, you know, gathering information that comes from people that are volunteering, uh, location information as part of the vocation history in Google maps for a good few years. And it's used to populate that little graph that you see on, um, what we call a place page in Google maps.

Ed P. 06:49 It will tell you relatively how busy this pub, this restaurant and this railway station is at any particular point in time. So what we want you to do is to take that data, which is already anonymized, but to aggregate that, to show changes in how population moves between particular sorts of places. So parks and transport hubs, you know, stations, transit stops, grocery paces and home. And, and to see what impact, uh, the, the changes that have been implemented over the past couple of, uh, weeks are actually having. And so it is, as I said, derived from those, those opt-in users of, of Google maps who are using the location history. Um, and it compares the, the changes that are probably, you know, on average two or three days old with what the situation was at the beginning of the year. So from that period, say from, you know, beginning of January to the beginning of February, that's the baseline. And we compare how many people are visiting parks, railway stations, grocery stores compared to that point.

Steven 07:55 And what level of granularity are you working?

Ed P. 07:59 Well, we report, uh, geographical areas. So in the UK it's a sort of a County and city level. In the States it's down to individual States and they're broken down into counties and regions within those that are sort of the geographical administrative boundaries that government agencies tend to,

Steven 08:19 right. You've probably got the data on my, how many people are going to my local Sainsbury's or my local park. But you're not actually publishing that data at that level of granularity.

Ed P. 08:30 We don't know. We don't have it at that, that level of granularity and we've worked very hard and it's taken us, you know, quite a considerable period of time to to make sure that we've come up with an information product that is driven by a user privacy and a lot of effort has gone in behind the scenes to make sure that the information that is presented has, you know, no risk of identifying an individual or having any kind of individual privacy concerns associated.

Steven 08:57 Okay, so you've got to what probably is going to be the question that lots and lots of people are asking. In fact, I can imagine some privacy zealots as I would describe them. Absolutely freaking out about the issues. I'm not, and I can, I can hear the voices in the background in a post. Oh, the Google AI blog. I'm going to quote this, your people say in line with our AI principles, we've designed a method for analyzing population mobility with privacy prep, preserving techniques at its core to ensure that no individuals use a journey. Can be identified. We create representative models of aggregate data. I am applying a technique called differential privacy together with Kay anonymity. Now you sent me some homework over the weekend and I did, did read credibly complicated paper on differential privacy and I've gotta be honest, I didn't understand a bloody word of it. Well apart from the title, so give me a simple explanation. What are you actually doing with this data?

Ed P. 10:09 It is complicated, but there's a, there's a lot of logic behind it. So that'd be, let me try and explain it as best I can because it is, as you say, it's quite complex. So differential privacy is basically a mathematical approach to quantify how good you're doing, making data private. So it's a measure of the effectiveness of a query or an approach that you apply to data to make that data private so that an individual can't be identified for within the data dataset. So actually contact with a quantifiable measure that you can use to look at an algorithm or a process and say, okay, how well does this algorithm or process protecting an individual within that data set from, from being identified? So it was developed by some scientists at Harvard, Oh, probably 10 years or so ago. And in simple terms, what it does is it applies noise, adds noise as part of the analysis that you might be wanting to do to a dataset.

Ed P. 11:11 So it preserves the statistical information. So the, the, the pattern that you're trying to, to see remains valid within the data, but the noise, uh, has the impact that it prevents an individual record being identified as such. Right? So if you're doing this well, what differential privacy means that your analysis I carry out will be the same whether you as an individual are included in the dataset or not. Now that's still sounds a bit sort of prosaic, I suppose. So maybe a better example would be saying, let's go, let's say that as Jim MOBE, you managed a registration data set that created a database with the people that came along to GM all day, every, every month or wherever, and then that date set you had, you know people's name, you had their sex, you had their age, you had their email address, and it's not unusual.

Ed P. 12:04 You'd have a good rationale for collecting that information and perhaps someone was interested in doing some analysis from a diversity point of view and said, well, can you let us look at your data set? And we can see the diversity of the people that turn up to GMO every every month anyway, so we'll, okay, we'll give you that data, but what we'll do is restrict out the name and we're strip out the email to try and anonymize that dataset. Now what you might quite right you say is, well, hang on a minute, ed. If I have another data set that contains some of the elements of your dataset, even if you've stripped out name and you've stripped out email, I might be able to compare these two data sets and match them and then find out who was attending GMO. Gotcha. Now what differential privacy tries to do is to, is to add some noise into the dataset.

Ed P. 12:58 So it prevents that crosslinking but still maintains the statistical viability of the dataset. So with that, Jim will be example. What we might do is to say, actually Steven will take your record and we'll make you a few years younger and we'll take someone else in the database and we'll make them a few years older and maybe we'll change my sec so I'll change from being male to female. But someone else in the dataset, our change from being female to male, and what you do is you add noise using what's called a a plastic statistical distribution, which is a bit like the normal distribution. You see, you know the bell curve you would expect to most datasets, but it's, it's double X, double exponential, so it's more more effect on the mean values within the dataset. And so you add that noise, you kind of manipulate the data sets so that you know, individual records will change. There will become a little bit more fuzzy, but the actual amount of information remains the same. You still get the same statistical distribution you get, but you've modified the records. They can't be identified in -inaudible-.

Steven 14:02 Okay, so it makes sense. So you have the same name, you'd end up with the same number of men, male and female in that data set with the same distribution of ages in that data set, they'd be all swapped around each record so that you wouldn't have the same correspondence.

Ed P. 14:26 Not necessarily all of them. Someone would be somebody who would be, you know, yeah. It's to -inaudible-. You know, the other element of, of that process is K and M is an immunity you said. And that that basically says, well within the dataset that you've, you fiddled about whether you want to make sure that there are key records that are exactly the same. So you then go withK individuals in the dataset have exactly the same content. So you couldn't tell one from the other within that dataset. Uh, so, soK anonymity means that you need quite large datasets to make this work. Uh, so it's not something you could probably do realistically on the GM orb registration database because there are alternative freckles.

Steven 15:09 But if you've got a million records.

Ed P. 15:11 Exactly.

Steven 15:13 So the kn unlimited means you end up with the same number of males and the same number of females.

Ed P. 15:18 No, it means that the thing about differential privacy is you get to choose how well you want to protect privacy. So there were, there were two values you'd deal with. One is, isK anonymity, which says, okay, I want K number of records that are the same. So for example, you might say, Oh, I wantK anonymity of a hundred. That means that within my dataset, there will always a hundred records that will have the same value in them.

Steven 15:46 Gotcha.

Ed P. 15:47 And you also then have a value called Epsilon, which is the measure of how well you are maintaining privacy and you can kind of change the value of of Epsilon to say, actually I want to add more noise and therefore increase the privacy value. But if you can imagine if you added lots more noise, you start to actually mess around with the distribution of the data and it becomes less accurate. So Absalon there's something that you can kind of twiddle with to say actually, you know, in this case I want an Epsilon value of two, which means that there's a fair amount of privacy, but uh, I'm not really messing up with the statistical accuracy of the data.

Steven 16:26 Once you've done this differential privacy process to effectively prevent the data being de anonymized later on, you then aggregate it as well.

Ed P. 16:36 Yeah, I would, aggregation may well be part of the process that gives you the differential privacy. So differential privacy is as if you like in the measure of how successful whatever process you've you've applied to the data is and uh, so that, that process might mean made up of adding random noise. Uh, which is, which is a main part of this. But it also may include as you say, changing in effect the space shade, temporal resolution, aggregating the data both in space and time, which is, which is something that you can do kind of uniquely with geospatial data that you couldn't do with, with other datasets. So that actually you know, adds another level of privacy.

Steven 17:16 My simple take on that is there's really not a lot to worry about here. And here's the question somewhere Google started off with a load of individual records and how can we be sub the Google wouldn't provide an aggregated data to a third party or a government, particularly if the government tried to legally compel it.

Ed P. 17:42 Well, I mean I guess you need to differentiate between you know, third party and the government cause they don't point

Steven 17:48 I the third party

Ed P. 17:49 less tech making data. Yeah. Making data available to third party is strictly controlled by all of the various privacy regulations and the terms and conditions that, you know, Google has over any of its data sets. So, you know, that's, that's never going to happen. That will make data available to a third party, you know, in these circumstances. I mean, the point around, you know, or crest by government agencies as well, you know, at a fundamental level we, we have to abide with the law as it is in any particular jurisdiction. And in some jurisdictions there is a requirement for any information collected by an organization like Google to be a made available upon the presentation of, you know, a valid warrant or, you know, a valid process through the legal framework in that country. Now, what we can do to minimize that is to make those requests as, as restricted as possible.

Ed P. 18:44 Uh, and there's, you know, there's a peak as you probably would have seen, you know, just looking at the web, there's this, uh, concept that's emerged in the state. So this idea of geo fence requests where government agencies will say, well, uh, tell us all the people that were within this area on this particular date. And we pushed back on those. So when are you need to be much more precise in these, those Y who you're looking for and so on. Uh, but the fundamentally, you know, if, if we have data around, you know, data subjects and there's a legal request to do that, we, we have to go through the process of, of potentially making that data available. That's something that that really does concern you. Then, you know, all of this is up 10, you know, you don't have to use the location history function. It's something you have to switch on in Google maps to start to record this nation. So fundamentally that's, that's the, the primary mechanism you have.

Steven 19:41 And I discovered that unfortunately I hadn't switched it on. And I went for a walk a few days ago and stopped to have a phone conversation with one of my kids and got my glasses. And by the time I got back, I couldn't, couldn't remember exactly where I'd been standing and had I had the location history or I would have probably had been able to see where I'd stopped for 10 minutes and being able to find my glasses. So I've now switched my location sharing or location history on and now I'm contributing to the next release of your community mobility reports. But yeah, you make,

Ed P. 20:25 and I'd like to thank you Steven, and I think everyone, you know that there's this huge value. I think we as individuals get from doing this. You know, I love looking back and I'm working out where I was, uh, you know, any particular day in the, in the past. And, and you are providing that, that community benefit in terms of, you know, this information here about mobility under these, but it's also what powers, you know, fundamentally, you know, all the information about real time traffic. So, you know, there is a real virtuous circle here. The bye, bye contribution, this information, you know, you are, you know, making, you know, Google maps and the other services that take similar approaches.

Steven 21:04 Yeah. And I think it would be fair to say, but at this point in time we might be less worried about that in the UK than people might be in, I don't know, some repressive regime, I won't name a regime, but there are more repressive regimes where you might think twice about switching this kind of stuff up. And also I, I guess if I, if I want to, I can impact, I know that I can because I checked before I switched it on. If you want to, when you switch it off you can also opt to have all your history deleted.

Ed P. 21:40 You can and there there were various levels of of functionality. You can have it deleted after a month or six months or you know, you've got complete control over that. It will, it will automatically delete, you know, your historic data if you want to. And you know, it's, it is, you know, information that is protected very, very securely within Google. We recognize it as being, you know, very, very sensitive and you know, can see what we've done here with these mobility data reports is, is we've been very cautious in terms of the data that we're presenting is being presented at a, at a very abstracted level. It's being presented as you know, paper reports as opposed to, you know, access to the real world data. So we are being very cautious about about making this information available. This, there's probably lots more value in detail within these data sets and you know, in due course I think society will, you know, perhaps, you know, become more grounded in, in the use of this information in the future. And I re, you know, I think there's a really interesting topic about the, the ethical use of, of this sort of location data, uh, moving forward. But you know, where we are at the moment, you know, privacy is all important. So you know, what, what we're doing to, to make this information accessible is going through many, many privacy hoops. And we now I'm super confident that there's this, there's no risk whatsoever with this data of, you know, an individual being able to be identified from it.

Steven 23:10 So you couldn't use this data for the sort of contact tracing exercises that some people are applicating for example.

Ed P. 23:18 Yeah, I mean contract tracking is a, is an interesting use case. It's something that, you know, probably any of the Truitt two data set, uh, the, any of the approaches that we're talking about here, which you know, primarily use GPS Wi-Fi cell by cell based location, none of that is precise enough for contract tracing. You know, I think there are approaches that you could take using more of a sort of a proximity-based approach using sort of Bluetooth Le functionality. And I think that may well be a direction that, you know, governments end up pursuing to maintain a, a core more robust at a contract. A tracking system did that. So that's actually quite a different technology to what we're talking.

Steven 24:02 Yeah. Just to take an interest for me, how long did it take you to pull these first reports together from the time somebody had the idea that you could provide some kind of measure of mobility change to when you actually released them last week?

Ed P. 24:17 Well, I mean it had been stuff that we've been investigating from, you know, the broader perspective of looking at urban mobility patterns. So we know we've certainly done the homework to work out how we could make this data available with a, um, a strong sense of privacy. And we, we've managed those processes and, and we've been looking at how do you do the analysis about how people move around the planet. Probably be towards the end of last year. If you dig, and I can certainly send you the link for this that you could put in the show notes. There are research reports that actually went out in, in nature about this sort of approach for doing mobility mapping towards the end of last year. So a lot of the groundwork had already been done. Uh, in terms of putting the reports together, it was probably two weeks, maybe just about three weeks.

Steven 25:09 It was very timely that you'd been doing that research last year, wasn't it?

Ed P. 25:13 I don't think it goes to that point. You know, I think there's this huge value in, in doing this from, you know, all sorts of different use cases, you know, be urban planning, you know, be it, you know, obviously you know, epidemiology and so on. There's a real value, there's real insights that can be obtained from this anonymous data that's aggregated at a level that's still, it's still quite valuable if you're talking about, you know, one kilometer grid cells around the planet. That's, that's still quite a lot of of useful information that has, you know, no, no risk for the privacy of, of an individual in that dataset.

Steven 25:49 And in fact, if you want to use this data to as a, an influence or evidence in policy making, you don't want it at a granular level cause you can't have policies set at such a granular level. You know, I mean the city level, I can imagine New York is, you don't really care about every grid square in New York. You're going to make a policy for the whole of New York city, aren't you?

Ed P. 26:15 No. And it's fascinating. I mean, one of the port, so I'll link to look to the hierarchies of, of cities and it goes back to, you know, I'm a, I'm a geographer by training and it goes back to, you know, the original crystal, the model of urban morphology and how cities develop. And you know, that was, that was kind of a simplistic model. But with this data you can see that, you know, many cities don't have one single core anymore. They're much more, you know, multimodal still are a hierarchy of places within a city. But it's not about the core and the periphery anymore is, is more nuanced than it's is fascinating. You know, it's his good old fashioned economic geography, but we suddenly have a different insight to that with this new new source of information.

Steven 27:00 So have there been any surprising insights that have come out of the community mobility report so far?

Ed P. 27:09 Yeah, it's funny. I think it varies. Obviously we would expect, you know, geographically but, but not so much within within country. If you look across the UK and probably you've, you've flicked through the data, you know, there's not a huge amount of variation and it's uh, you know, brought a smile to me when I, when I looked at the data for the first time, because I think you'd been tweeting about, I think you and Ken have been tweeting about when is it appropriate to use a map and when not, and this would be one of those examples where in it probably a map isn't that appropriate because actually there's not, you know, within the UK a huge amount of variation. So there's not really very much to make them Apple, but there are clear variations between different countries. You know, you can compare, you know, UK and France very similar in terms of the change is quite a marked difference. Say with, with California, which has had a, a smaller amount of change. And then, you know, Sweden is an outlay or an outlier. And if you've been watching the news, you'll know that, you know, Sweden has taken a different approach to social distancing and that's reflected in the data.

Steven 28:11 Yeah. And now they're changing their mind, aren't they?

Ed P. 28:14 Oh, who knows? Yeah. I think that's, you know, that's part of the problem here. You know, we're all, we've all been making many of these decisions, you know, it's government agencies a little bit in the blind and, and you know, it's hard, you know, I'm not an NPU mineralogist I'm not an expert in health science and public health, but I imagined, you know, if you were involved, this must be so frustrating having to make these massively complex and decisions that have huge impact on, um, countries with w, you know, with so little data

Steven 28:44 and probably knowing that there's no right decision there only less worse decisions.

Ed P. 28:51 Yeah, yeah, exactly. Yeah.

Steven 28:53 So let's, let's look forward just a little bit and imagine that the, you know, we're at the end of the year, hopefully the virus, if not completely gone, it's past its peak and life is getting back to normal. What other ways do you think these mobility reports will be used once we're out of this? Um, this crisis?

Ed P. 29:17 Well, I don't, I think these particular reports will disappear. You know, once particular health emergency has disappeared, will stop producing these reports, but then we'll probably sit back and say, okay, well how did we, do, you know, what was the societal impact of doing this? How did society view this sort of information? What were the privacy concerns? And you know, my personal hope, and this isn't by means guaranteed or you know, no way expressing, uh, a future policy of Google. You know, I hope that we, we see the value in these sorts of, of information products and salt to think about making more of this information available to, you know, different communities, be they, you know, those involved in government in town planning or transport strategy or you know, at a, you know, at a more commercial level about understanding, you know, footfall and all of that information that you know, currently is collected by, by someone sitting in a deck chair with a counter on the high street.

Ed P. 30:18 We could be much more sophisticated about that. But you know, I recognize that this is still, you know, very challenging territory from the point of view of privacy. You know, we still are highly sensitized to this, but I think, you know, it's something that we are going to get more used to. And you know, the, the comment you made a little bit earlier about contact tracing may well be something that we separately will become quite familiar with. If the way out of the current crisis is that we all have an app on our phones that tells us, you know, who are interacting with, again largely anonymous week cause it doesn't actually identify individuals until there's a, there's an issue we'll probably end up getting, getting used to a lot of this sort of data. But, but you know, I think a lot of those drivers will come not from commercial companies, not from the platform providers but from, from government.

Steven 31:08 Yeah. And I think they have to, you know, I mean I think there's a legitimate question to be asked about what a bad actor could do with some of this technology. But at the same time, you know, when tens of thousands of people are dying around around the world, you know, and forecasts are of hundreds of thousands or even millions dying. If governments can use technology that infringes in some way on our privacy but protects us in some way, then I think it's a trade off we have to consider.

Ed P. 31:41 I think you're right. And you know, in some ways I guess it kind of reflects on the debate we've had in, in the UK over the years about, you know, CCTV, you know, uh, there were huge concerns about the, the, the spread and the, the use of CCTV. I think we've sort of come to terms with the fact that it's there and it does have an important role in public safety. So maybe a similar approach will, will happen here, but it's a debate that we have to have. And I think as the geospatial community, we've often tried to shy away from some of these ethical questions because there'd been maybe a bit too difficult. We didn't think we need you to have those discussions, but, but you know, it's really been highlighted, you know, over the past, past month or so, and it will be up there as a sort of priority of, of discussion over the next six months for sure.

Steven 32:30 I'm sure it will be. I mean, I think just wrapping up, first of all I want to say I think it is absolutely incredible that the technology that was quietly giving me the traffic information in my Google maps when I was using it to drive somewhere or the technology that was telling us what were the busy hours in a shop or a restaurant or something is now able to tell us, give us an insight into how effectively the social distancing policies of various cities and governments are working. You know, that's a remarkable achievement that we've had that. And um, you know, I think, yeah, personally I think Google should be congratulated and I want to say thank you to you guys for everything that you've done. It's been a pleasure, ed. I feel very honored that we've got you here talking in such detail. And so candidly about the work that Google have been doing. I'm sure our listeners are going to love listening to this S so. So let me wrap up by asking as standard closing question. As somebody who's been to quite a few geomobs going right back to the very early days, have you got a favorite moment from geomob?

Ed P. 33:43 I don't have a single favorite one and I think I've, I've not gone to anywhere nearly enough gym modes. I think the thing that I probably like most is just the diversity. You, you'll never quite sure who might turn up. And you know, to be honest, I've probably not been to GMO for, for two or three years. I've been, I've been traveling so much, so there's part of me that's actually quite excited that you're going remote and you're doing this online now because it will allow me to, to have a much better chance of being there, you know, at least virtually in a room to, to participate. Uh, it's, it's the diversities, the interesting folks that turn up to do presentations that you were not expecting that I really value so much.

Steven 34:27 I absolutely agree with you, and not only are we going online during this coronavirus, but um, we're going to be recording the whole thing. So for the people who didn't manage to get an invitation to the live event tomorrow evening, for example, they'll be able to log on in a couple of days time and we'll have that whole thing up on YouTube. Of course. Final thing in case people want to get in touch with you and ask you questions about this stuff, what's the best way to get in touch with you? Just Google me. I come up. Okay.

Ed P. 35:04 I'm ed Parsons on most platforms, so yeah, you should be asked by me.

Steven 35:08 Okay, fine. Great. It's been my pleasure. Thank you very, very much. I look forward to seeing you once the lockdown is over and we'll have to get you talking at geomob soon after that when we can all get back together and drink gas after a GM. Take care. Thank you. Likewise, Steve. It's been a real pleasure. Thank you so much for the opportunity. Pleasure.

Ed P. 35:33 Thanks everyone for joining us today and listening to the GM on podcast. I believe, enjoyed the discussion. Please

Ed 35:38 don't hesitate if you have any feedback for us or any suggestions for topics that we should cover in the future. You can get the show notes over on the website, which [email protected] while you're there. If you're not yet on the mailing list, please do get on the mailing list where we once a month send out an email announcing future events, summarizing past events and just generally sharing, uh, events that you may find of interest. You can also of course, follow us on Twitter where our handle is geomob. You can follow Steven at Steven Feldman. You can follow me fry Fogel, you can check out Mappery at -inaudible- dot org and of course, if you need any geocoding, please check out my service, which is open cage data.com. We look forward to you joining us again at a future episode or end of course seeing you at a future geomob event. Hope to see you there soon. Bye.