Subscribe

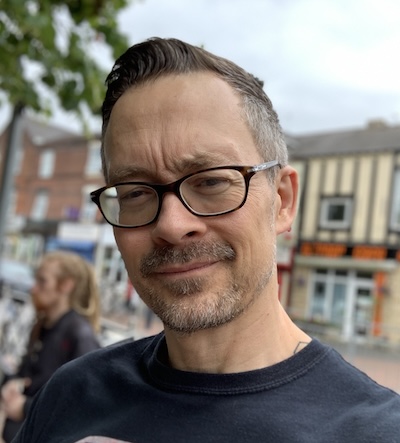

This week Steven chats with long-time geomobster and data expert Giuseppe Sollazzo. Giuseppe is Head of Data at UK Dept. of Transport, curates a widely-read weekly newsletter about data, and organizes Open Data Camp. He spoke at Geomob London in July 2016.

Relevant links:

About the podcast

On the Geomob podcast every week we discuss themes from the geo industry, interview Geomob speakers, and provide regular updates about our own projects.

Popular podcast topics:

The Geomob podcast is hosted by:

Autogenerated Transcript:

Ed 00:01 Welcome to the geomob podcast where we discuss geoinnovation in any and all forms, be it for fun or profit.

Steven 00:11 Welcome back to another geomob podcast. Today I'm joined by my good friend to say this a lot, so otherwise known as -inaudible- on Twitter. And we're going to be talking about open data and stuff, but before we do talk about that, I just better introduced your Sepi to those of you who haven't had the pleasure of meeting him. He has a fascinating biography born in Italy. He arrived in London in 2008 to start a PhD at Imperial college but dropped out after a few months. Then he was a senior systems engineer analyst at st George's university and while he was at George's he became very involved in the open data movement in London. And for the last year and a bit, Giuseppe has been head of data at the department for transport. So that's quite a CV. Um, good morning to you.

Giuseppe 01:14 Good morning Stephen. Thanks for having me on this podcast.

Steven 01:17 It's a pleasure. So first of all, tell us what you were doing at st George's.

Giuseppe 01:23 So listen, George is, I said I got to st George's after I quit quite abruptly. My, my PhD about six months in and at the time where there was a financial crisis going on, there weren't many jobs available. I still wanted to be somehow close to academia for a variety of right and wrong reasons. And so yeah, I found this job as a systems developer at the time doing a bit of support to the the server farm and to research computing. Uh, and I got promoted over time and basically I was looking after all the classic assistance side of a relatively large medical school. So you know, emails, calendars, uh, web servers and also the research computing side of it. So over time I worked on quite exciting things like setting up high performance computing as well as still keeping all our services running on time. I was sort of leading our second line of support, so engaging with people, having trouble with things, ranging from emails not being delivered all the way down to how can I do this heavy type of computation on my proteins in, in, on your service. So it was quite a broad set. The old tasks that I was dealing with was quite exciting

Steven 02:41 Book, some quite deep geekery there as well from the sounds of things on the research side.

Giuseppe 02:46 Yeah. Yeah. And that's what actually what kept me in the job for a long time. The, the fact that I was working on this incredibly geeky problems, some of which had to do with you know, neuroscience or with know just with, with Bay basic, making sure that the Samba shares were working, um, while also having a big opportunity to learn new things. Uh, hands on. I had the pleasure of working on my manager wasn't incredibly a technical person who was very keen on, you know, developing people and I really enjoyed working there for, that's why I stayed there for about 10 years. What's interesting is that one of the reasons why I applied to that job was that I wanted to stay close to academia. I still dreamt of at some point going back to a PhD. And then I realized over time that what I really liked of the academic life was the ability to work on something you know, you're passionate about while solving their relationship with people who were very no intelligent, done and successfully the field. And I sort of got that to a, a very technical job. So, uh, I sort of over time started thinking, well, maybe it wasn't such a bad idea to move out of being an academic myself.

Steven 03:59 Uh huh. And whilst you were at st George's, you founded open data cab, didn't you?

Giuseppe 04:05 Yeah, although that wasn't my first venturing into open data. You know, it's a sort of a convoluted and complex story, which starts with, uh, working closely with, with our library. Actually. I said Georgia, uh, they, they were working on, you know, this, this thing called open access at the time. So the idea that papers, academic papers should be somehow accessible to everyone. And by doing that, you know, we, we started thinking on the idea that the datasets of that triggered the research or that were assembled during the research should also be free. And now all of this was happening, as I said, around 2009, 2010, which is the, the, the period in which social network called Twitter. So that the social nights or to which, uh, we met, uh, at some point, um, was starting to be quite popular in London and it will start to be popular in specific networks of people.

Giuseppe 04:58 And those networks of people were government people, academics, uh, you know, overall geeks. So it will still a sort of a niche social network with all, I think the right people in a sense to, on there. Uh, and open data was starting to be a thing as well. Um, so I sort of, you know, one thing I've always liked to do in my career was actually to connect people and uh, and things from, from different areas. And so I saw that connection between, uh, the open data that was happening, uh, in the government, in the public sector and the government and the open access, uh, happening, uh, in academia. And therefore I sought to make that jump. I, I found that open data was an interesting community of people. And after a while to get with Mike Brackens was at the time, uh, working in a local authority, we started thinking, well, we might need a way to get all these people together in a room to, to make them engage in a sort of a relaxed way. So we thought, well, an unconference would be the best way to do this. And that's how that account was founded. And that was 2014. So now six years ago, and we've done quite a few of them.

Steven 06:04 Fantastic. And how many people did you get to one of those?

Giuseppe 06:06 So the, uh, we, we have actually records for attendance and the, the highest record was in Belfast. We run open at the camp in Belfast. We had about 122 people, if I recall correctly. That was amazing. You know, also the, the big advantage of, uh, being reachable by, by two countries. So, you know, people from both the UK and the Republic of Ireland attended, uh, it was, uh, quite a good, a good event. But we have over a hundred attendees also in Cod. This despite the terrible weather we have that weekend. Yeah, we have 88, I think in a, in Hampshire in Winchester. A lovely place to run an unconference. Pam, it's been quite well attended.

Steven 06:46 And what kind of people come to these events? Are they all government people or do you get a broader mix of people?

Giuseppe 06:53 Ah, well that's, that's a few like, uh, generalist people who are in like overall geeks. We have a good participation for people who are involved in open street map. For example, two people who come from different aspects of open data, whether they are now, they might be people who work in where with councils, uh, you know, uh, GIS managers in councils have been a constant feature of -inaudible-. Uh, we have Gates, we have developers, we have people interested in policy. We have, uh, academics like, you know, you know, Babar for example, we have the one point pull molded, uh, who was at the time director of the, uh, government data program. Uh, he came there. I mean, we always recall this sessions where everyone attended those sessions and we called them the unconference and keynotes. Uh, and they were particularly successful. I mean, I think that that was really good. We also had the permanent secretary attending in Belfast, which was quite an interesting thing, uh, to see, uh, a variety of people that have attended over time.

Steven 07:56 But importantly, you, you've got interest from some fairly senior people in government and government technology.

Giuseppe 08:03 Absolutely. What was interesting to see is how, uh, although the, uh, you know, open data might not be high up in the, in the agenda at the moment. I mean, there's a number of other things that happened, uh, after the, well, yes, quite a few over the past three years. But what's interesting is that the people who firstly engage with open data have somehow understood that there's a better analytical way of going about things, policymaking and operations and all that. Um, and I think that the conversation that we're sort of initiated by the open data movement have been, I've made partner a lot of roads inside government and, and that's really good.

Steven 08:45 Yeah, I agree. So let's talk about open data for a minute. You and I spent many, many evenings with a glass of beer in our talking about open data and, uh, the things we agree on and I suspect they're things we disagree on, but most of the time we agree. So start off explaining what you mean when you refer to open data.

Giuseppe 09:09 Well, I mean, open data there is a quite well known and very broad definition and by the open knowledge foundation about open data being a data coming from whatever source that is generally machine readable and attached to an open license. Um, but you know, the, uh, the different, uh, phases of that definition can acquire very, very different. I mean in government would generally mean data that's been released under the open government license. So I would say, what would I refer to open data is normally data that is somehow openly accessible. Um, for me, open data is mostly, uh, public sector data, although even that, uh, you know, on the spectrum so that there are, you know, the quangos some, some of the quangos release interesting data. So he stopped government data and not, uh, hard to tell thought. Um, there's, I think there are two ways of seeing open data in general.

Giuseppe 10:01 It's um, say the two ways are on one hand data that is published because of a transparency requirement. So for example, data around government expenditure. And on the other hand there is data that comes from running certain operations or data that uh, you know, pertains to a specific type of task. So for example, if we think about mid office data, that would be the type of upstate that I'm thinking of and these two concepts, you know, transparency and operations, um, somehow, uh, engage over time and there are different parts of the open to the community wall who care about different aspects of them.

Steven 10:40 And mean you didn't mention accountability, but I mean, I think within the open data community, sort of the people who were outside of government but who are often advocates for openness, accountability is a very, very big factor for them. The ability to hold government to account maybe slightly different to transparency.

Giuseppe 11:03 Well, yeah, because you can take public authorities to accounts by not just seeing the way they spend in money, but the way they run their operations. Now, I shouldn't be getting into too much into this discussion, uh, given my current employer. But, um, I think it's fair to say that there are many ways we can monitor, uh, activities of any public authority. There is one major aspect of open data. I think that's the way we engage with open data has evolved over time. And the, the maturity of the open data movement is evolving as well. And so there are aspects that, you know, at the beginning of the open data, you know, when Charles Salter and the guardian were doing LD the free out data campaign, we're probably thinking around, you know, government has data. They need to publish that data. Um, no matter what.

Giuseppe 11:53 But over time we also started to think about, uh, ethics, uh, about trust. Uh, and there are all concepts that are in evolution. And you know, the reason coronavirus crisis has probably produced a certain spin in that discussion as well. Uh, where we seeing, you know, for example, the South Korean government tracking people with apps without too much of a controversy around that while in Europe, no one is doing that because the, the approach we have to, to trust and ethics is like different. So there are also regional variation to that discussion. And I think that's what makes it very, very interesting. And uh, it, you know, opened it, there's not a, as I say, a complete thing is something that evolves together with, uh, the, the needs of people on the ground. It evolves with events like pandemics for example, and evolves with, uh, technology as well.

Giuseppe 12:44 So, uh, 10 years ago we didn't have facial recognition, for example. We now have it and that clearly changes a little bit. The, the perception we have around data releases in many ways. You know, you, you probably have seen a few years ago I did this, uh, uh, entertaining thing about calculating the average Faisal of member of parliament. It went viral, you know, have like all the fun doing that. But now, you know, I'm sort of thinking is that ethically, you know, is he ethical to have a laugh or based on the average phases of people who are elected and therefore as a reflection of an entire nation. I mean, I'm not saying it isn't, but this is a question and now I'm asking myself that when I did that, I wasn't asking myself. And yeah, those questions will evolve all the time.

Steven 13:32 Personally, I think that a lot of the ethical issues are more linked to technology than to where the data is open or closed. You know, I mean, the fact that we can now use AI or whatever too completely fabricate video, but we can then broadcast, you know, is a much bigger concern to me than somebody playing around with, uh, government open data and possibly crossing an ethical boundary. You know, I mean, I think that the technology is, is sort of moving the boundaries the most enormous pace at the moment.

Giuseppe 14:15 It is. Uh, and that we know it's all about, I think the, uh, the principles clearly, you know, probably there aren't many government datasets that will cause that sort of, you know, excitement, uh, as you know, the technology behind the generating faces. But, you know, I wouldn't be surprised if if he found out in a few years time that data as ma as been sort of misused to do that. I mean, I think the problem is that we, we don't know and we need to be ready to, to ask new questions as they, as technology evolves. Uh, and you know, w without also believe in the hype. I mean, now we both remembering that there was a time where every single problem of society, we thought it could be sold with open data. And, you know, we, we sort of now realizing it's more complicated than that,

Steven 15:05 More complicated than that. And up, you know, I think in the current coronavirus crisis that we're going through, you know, there's been a flood of tech and data people coming out with their own ideas of how to solve the problems and how to deal with distancing and reporting and whatever else. And, you know, I mean some of these apps, I was looking at a couple this morning before we got on this call, you know, and some of these apps just aren't being used by anybody. You know, loads of people do loads of work to produce these things and nobody actually gets to use them because cause they're useless. You know? And I think there is a,

Giuseppe 15:43 We could, we could go back to that question, the, the classic GDS question, which is, you know, we'll see. Use a need. And I think there is a understanding that the situation of current Novartis as evolved so quickly that, you know, it's been really hard to produce fast responses based on data. Like, you know, we've seen the, the various, for example, mobility in this is produced by the Citymapper, the Google, the uh, the move it and all those apps. They very useful to see that people are not traveling that much. Uh, and, and clearly that, you know, in the first phase of the crisis it was very important to, to, to verify, you know, whether the lockdown measures were working. I think I've seen the same in Italy where luckily the, the rates of infections, I've gone down massively a couple of weeks after lockdown.

Giuseppe 16:29 So, you know, sort of confirming that the lockdown was working. But now we are in the phase where, you know, we might not know when life will get back to normal. I mean, we were seeing all this fantastic press conferences every day. I'm really interested in, aside from my, from my work, it's interesting to see how government is now using data on a daily basis to, uh, uh, to respond to the journalists question, which is something that absolutely I think positive regardless of, you know, people's position on whether we're doing that good or bad. But at the same time. Yup. Go ahead.

Steven 17:00 The only problem that I see with government using data to respond to journalist questions is when they pick and choose what data they're using.

Giuseppe 17:11 Well I can't comment on that

Steven 17:14 But I can't, you know, I mean I think there is a data set which if you sample it will prove almost anything that you want to assert, you know, and um, I mean it was interesting how long it took for the ONS data on weekly death. Right. Two be brought into the conversation. So now we're, we're talking about excess deaths over the five year rolling average of excess debt of deaths in a week.

Giuseppe 17:47 I think it's fair to say that this is really hard and you know, the scientific consensus around what data is more important. It's been evolving as well. I mean, you've probably read the fantastic articles written by David's big law healthcare, you know, who has highlighted that problem about the way that's are recorded in different countries and therefore how difficult it is for example, to compare countries based just on, you know, Kobe recorded. That's, I think that that's very important. I mean, once again, it's not about politics, it's more about the fact that there is a lot of uncertainty even when data is recorded according to the, the current procedures we have. So yeah, I think I'm still quite positive and, and you know, happy to see that data is being used at the same time. Going back to what I was saying about the using the, the actually the, the ways we will respond to this crisis over time clearly, uh, will change.

Giuseppe 18:47 You know, like in Italy for example, they're talking about the face. Do not, I mean my parents have been in lockdown for about six weeks. They're now, you know, seeing the, the light at the end of the tunnel. But we're still talking about a pandemic for which there is no, uh, you know, Clare therapy and therefore, or vaccine vaccine. I mean we don't know how long that will be before, before something that is available and therefore we need to start thinking, you know, what would be the best way to keep monitoring the way people travel, people moving out in the scenario in which we need to get back to life more or less as normal. What that, how big that more or less is, is going to be relevant. And therefore, you know, we might find yourself in a situation where we actually want to measure sort of distancing in the park.

Giuseppe 19:32 How do you do that? You know, do you send people with, with the ruler or using those CCTV cameras to identify faces? You know, I've done a bit of that for fun about identifying faces in photographs and it's not perfect. No system is perfect and you know, the degree of uncertainty is going to be one problem. The other problem is going to be trust. You know, will people be happy to see people with a ruler? Will they be happy to see CCTV cameras? Uh, and you know, once again, the, those, you know, the relationship with that evolves with time, evolves with the nature of the problems, try to solve, you know, the, that, that the concept of the Overton window, that interest in politics, the reason Overton window of technology used by governments, uh, to address societal challenges and therefore we need to be, you know, looking at that. The one thing I'm sure about data is that no one has become rich with open data. And you know,

Steven 20:31 That's, you just touched on one of my favorite subjects because if we go back 2009, golden Brown and Tim Berners Lee, you know, there were, there were three, there were three, four to, to the open data movement. You know, there was transparency, there was accountability, there was innovation that people would find new ways of doing things, improve service quality and all of that. And then there was this belief that I'm opening up data would some enormous creative talent and um, new businesses would start and it, yeah, people were saying 6 billion pounds worth of economic benefit from open data. If only we'd had, if only all the survey data had been freely available to everybody, Google would have been created in the UK, not in America. I mean, it was, I mean, to me it was bullshit, you know, and I was outspoken continuously about that. But

Giuseppe 21:40 Now you're to remember I was on the other side of all of this and I was, you know, using all of this. If only, uh, then over time, you know, we realized that there were too many, if, uh, in that discussion, and I still think that, you know, certain data sets should be made open. I understand that the challenge is to do that some times are really hard. If there are legal problems, you know, that there was that famous situation with a land registry releasing the price paid data, that fantastic dataset by the way, uh, under OGL, uh, and then only realizing that the, you know, the, the, the were addresses in there and the addresses were clearly not on the road yet. I mean, there are complications in there that it's really hard to, uh, to deal with, uh, without massive investment to begin with.

Giuseppe 22:25 Uh, and therefore the question is, is it right to spend the money to do, to the spending public money to do that or should we spend money on something different? You know, there was this old attempt, for example, at creating an open addresses, uh, database. Uh, I remember that that was part of the panel that assigned money to that project. And, you know, it was exciting. We learned a lot about that. But at the same time, we also learn these very hard to, to make a business out of, uh, something like, uh, a new open addresses dataset. So, yeah, I mean, I don't know. I don't think that open data in itself is a way to, to run massively successful businesses, but you know, you know better than me that success in business is determined by the ability to innovate and sell a new thing to people rather than, you know, it doesn't come for free just because that's a data release.

Steven 23:20 Yeah. And I still maintain that if your, if your business proposition is really strong, it probably can afford to pay a commercial rate for any data resources that it needs. You know, I mean, that one could argue what our commercial rate is. But you know, I mean, I, I've never thought that people needed free data for everything to build a business. You know, there's not much of a business, a bit can only run on free data. But let's just before we leave open data, you've been doing this for 10 years now. If you had to sum up the state of open data today, how would you sum up the state of voter data today?

Giuseppe 24:04 So I think there's one thing to be said. So open data is still important and it's still important for me in the original meaning of more transparency, more openness because it's a way for governments to really engage with, with populations. And although we might not, you know, think that that's being at the moment particularly important in the Western world, uh, open data is still a big thing in, in countries, you know, outside our sphere, in many contexts, in Latin America, there are huge, in the civic technology organizations working on open data is becoming big in Africa. So, you know, the, the problem with open data is that often the, uh, Western world centric view of the importance of open data in countries that may be know how to read the, an established democracy or something like that. Okay. It may think it can make things better, but at the same time, there are parts of the world where you can literally change the way citizens and get engaged with, with their government and their authorities.

Giuseppe 25:05 And you know, we've seen some of that we were discussing previously when we were doing the military fair project, we would mock Carla's, uh, the fact that, uh, you know, uh, in, in, uh, in Islam, in Tanzania having the ability to, to share data about a toilet location, uh, is, you know, probably a matter of life and death while having a, an, uh, a database of public toilets in the UK. Well, it's a nice to have. It's something, you know, it's not particularly, they will, will not save your life as much as you want to think about that. So I think it's really important to, to do that. I mean, I'd like to, you know, to, uh, on this dimension, my friend, uh, more Rubinstein on, uh, Tim Davis who actually, um, edited this fantastic book called the state of open data, uh, which is available in a free forum on the web. Uh, really like everyone to, to have a look at that because, uh, you find out there's so much happening with open data outside of our Western world sphere.

Steven 26:00 Okay. We'll put the link of that Giuseppe in the show notes that go with this, with this episode. Just one final question on data, which is that you've been head of data, the department for transport for a year without going into anything that is restricted. Tell us what, because head of data at DFT do and what's that role mean?

Giuseppe 26:28 Well, it's a new role and I mean it was the, when when I started and basically I was asked to set up the data team. Uh, the department of transport didn't have a central function to support a variety of work streams we are dealing with in the data space. You know that the department, for example, publishes official statistics. Many of them based on data. There are data driven project, like new things like boss up and data. We have strict manager, there's a variety of work streams happening in that space, but there was no central function to support them. So what I've been doing over the past now, I think it's 15 months, 16 months, I mean time flies when you're having fun. Uh, so we started from one member of staff. We're now about 10. We are, uh, sort of trying to understand how to support the whole life cycle of data.

Giuseppe 27:16 So I have three small units reporting to me. One is doing, uh, internal transformation. So then we have the capital of product owners slash delivery managers. I have a technology team working on mostly data engineering problems. I have a small policies, less commercial units trying to provide a link between, uh, the policymaking and commercial opportunities for the department and outside. So, you know, it's, um, it's a very broad, very generally. So I, I do like being a generalist. So you know, this in a sense, it was a dream job when, when I saw it. Uh, I'm also working on, um, a transport data strategy, uh, which, uh, funnily enough, there is a video of me talking about that a, at a conference in October, I think it was. Uh, and you know, I made promises about the publication without that strategy, without thinking that, uh, an election was coming up or shuffle was coming up and then a epidemic was coming up. So the other thing I've learned over the past year is that you need to be ready to deal with, uh, whatever is thrown at you. And sometimes, you know, it's not nice things, hope it was entirely unexpected and it's sort of delayed my work on the data strategy. But once again, it's really interesting to see a department of IDFC putting in data centrally in its agenda. So it's been an exciting ride so far. And you know, I'm hoping to keep doing that for a bit.

Steven 28:38 And can you share any examples of how, yeah. The products and outputs from your data team have been utilized during the coronavirus crisis?

Giuseppe 28:50 I'd say that's still too fresh to, uh, to discuss. But I have members of my team working on, on response. Uh, and yeah, that's very interesting. Yeah.

Steven 28:59 And looking forward, you know, going forward a few years, what would you like to see being your achievements as head of data at the ft?

Giuseppe 29:09 Speculation. I'd like to see better discoverability of transplant data to begin with. Uh, I'd like to see, you know, more solid approach to policymaking. That's not just the ft. I mean I think data analysis needs to be central in policymaking. I'd like to see a better approach to data sharing between different parts of the public sector. I mean, sometimes it's really hard to, to work with, you know, agencies, local authorities because you know, each organization has its own goals, its own challenges and its own approach to data. I mean, it's clear to me that a policy during the department, like mine doesn't have the same worries about organizations that store a lot of personal data, for example. And therefore, you know, it, we need to work quite hard to understand how to bring forward a situation in which we can make better use of data while maintaining the public trust.

Giuseppe 30:11 And luckily, I mean there is a very good team of DCMS now working in the national data strategy where some of this project that some of these problems are being, uh, looked at, uh, from a more holistic point of view. So yeah, that's I think the future for me. The other thing is on the side of my job is to hopefully to lose that pervasive phrase and the data is the new oil, which I don't lie, I always do this job whenever someone tells me they test the new oil, I sort of respond a cheeky way by saying no, they, there's a new olive oil because to get value out of it, you need to squeeze rate of any hard and most of it will be incredibly bad quality. So yeah, I hope people will understand that. You know,

Steven 30:54 So Paul Copen data and let's just jump to open street map, which is data as we know, but um, it's geographic data that's crowdsourced and the dataset it produces. There's an open data set which anybody can download, analyze, visualize, use to produce new products. And recently you shared a hobby project which you'd been working on where you somatically mapped city road networks according to the road descriptors, I. E. Whether it was a street, a road, a closer Hill, you know, those bits that come at the end of a road description. Can you explain what you did and why?

Giuseppe 31:42 So first of all, I mean that, that's not my original idea. Other people have done that before. I think Erin Davis was the first to do that. Based on our, there are people who have done the same, uh, the same piece of work based on a queue GIS and shape files. So what they found fascinating was the idea that that same piece of work could be replicated in a, in a sort of automated way using a, a very good library, which I've used before for projects called OSM annex, which is a partner library, uh, that a, uh, an academic, uh, called Geoff Boeing has developed as part of his PhD thesis. So this guy is incredibly talented academic in the U S had to run as part of his PhD in geography, a set of network analysis of, of roads. And as a side effect of doing that, it didn't find any easy to use software to analyze, uh, open street map data and he developed his own and released to the public with an MIT license, which I think is incredibly thing to do.

Giuseppe 32:42 It's a bit, it's very nice. It's uh, it's progressed the uh, open source, it's the large open data agenda. Um, so yeah, when I, so what he was doing with, with this software package, um, I said, Hm, that's off the package. Could be used to do the same road coloring, which I'd seen others doing. And part of the reason why I try, so, um, it's funny that some people think I'm a creative creative developer. I'm not creative at all. Like what I like is replication and automation and I like sharing things in a way that people can then take my code on and replicated. So I'd say, you know, coaching people to use data and then, you know, advancing data analysis is one of my vested interests in all of this. So what they did was simply to create a Jupiter notebook. So it's a fully replicable set of procedures basically to just take, uh, the, uh, the data out of open street map and, and produce the drawing of the road coloring.

Giuseppe 33:39 What's very interesting about this, eh, as do things, I mean, when you say open street maps to people who are not part of our community, they think valve open street map is sort of the, you know, the Google maps, poor Coulson, we're actually, if anything is Google maps rich housing. So the open street map is not the map is the data that powers that map. And the fact that, you know, you can create that data. In many ways, OSM index is one way to do so is it's absolutely great and you know, you can do that on any, you know, I did that analysis on my laptop, uh, and it's, it's pretty powerful, I think.

Steven 34:16 So I was a bit cynical. Yeah. When you first shared the first map, I looked at it and I was a bit cynical. What's the point of this? So you can color the roads. Big deal. Yeah, we will know you could do that. You know what I mean? You could do that in Q, just, you can do it in lots of ways. But I recanted now completely, you know, I mean, let me publicly say on this podcast I was wrong. Yeah, I've seen and other people have pointed out that there are some really interesting insights coming out of coloring the, covering the roads according to their names. Can you share some of that with us?

Giuseppe 34:57 Well, it's interesting. I mean I have actually a collection of links of people who have responded to me with their own maps and I will share that afterwards. Um, but what's interesting, I think it's, it's a dual aspect of this. So first of all, I like the fact that there is data underlying a map. Uh, and you know, the, the query can be done in ways that you can basically just highlight very simply on a map. Uh, some feature. Uh, the other thing is, is you know, the aesthetic aspect of all of this. So I think it's, you know, I love maps. I mean, you probably do as well. We have a few friends who love maps and there is a certain pleasure in seeing, uh, a map take life. Um, automatically. Now the, the, the most recent, uh, result of all of this has been a friend, a journalist of mine, Duncan gear, who's actually currently based in Gothenburg.

Giuseppe 35:49 Um, and he's built a plotter and he's asked me to send them the, uh, SVG files from a few of my maps. And what is doing is basically doing live streams on YouTube or this plotter drawing, uh, which is absolutely mesmerizing. It's, you know, it's incredible. I spent like an hour looking at this plot, throwing the map. So I think there is a certain part of the community which is really attracted by the simple beauty of maps. So that's one thing. Uh, the second, the other thing is clearly as you say rightly, the insight that those maps can produce. Now, what I did once again was simply to put together a sector of know, very simple, replicable pipeline to do that with whatever location you like. And what I really enjoy was to see people starting to use my Jupiter notebook to, to do location. I I couldn't think of a, and then discovering different patterns. And what's really interesting is, you know, key o'clock did this before me. I think probably that's where you, you sort of pivoted to, to be in a support about investigating, you know, the history of how it was the pivot.

Steven 37:00 It was complete. UTA.

Giuseppe 37:05 I mean it was great to me because what I saw there, you know, a kid didn't use my code, they just use it an entirely different set of procedures and processes. But um, you know, the, the common aspect there is that you can discover things about the history of your place and there's this famous idea that there are no roads, I think in the, in the city of London, uh, which is actually just how through, because I think how far it goes, we're road actually belongs to the city of London initially. But there are reasons why the walls and know people can discover those things by just looking at a graphic representation of, of location, which basically that's where the map is.

Steven 37:43 I just to sort of articulate that, that pattern for our listeners, it appears that certainly in an English context, cities as cities evolved, we had streets in those cities and roads were the things that joined clusters of habitation up. So the roads joined cities basically, and city centers were streets and gradually the other suffixes like way and road. And haven't you all evolved over time. And if you look at, um, these beautifully colored maps, what you can see is a visualization of how the sister year the city evolved over time being displayed through the road suffixes.

Giuseppe 38:35 Yes. And it's something that you find a lot in, uh, in British, uh, cities, but not elsewhere. Like, you know, once again now, it's not the looking at Italy thinking, Oh, I'm going to do all this beautiful maps of Italy. But it turns out that the way cities were built in Italy, uh, you know, in many cases you have this pervasive via, as you know, a qualifier of a, of a street name. Um, in part because that's the most common way and it's way more common that the site strict the roads in English. Uh, but partly because many cities were bombed and when they were rebuilt, you know, the, the, the, the roads changed completely. Names and India was the, the most popular suffix at the time. Well, I'm trying to look at now is basically, uh, older, uh, cities. Like, you know, we have a capital of world cities in Italy and, and see if there's any difference in that.

Giuseppe 39:25 I mean, there's a few places which, uh, settle out roads, cold Sada, so the equivalent of streets, but, uh, which you need to live normally use for older, uh, roads. And at the same time, out of the few friends who are based in, uh, in Finland and Sweden who started doing that, uh, with the local, uh, suffixes, which is interesting because you have similar patterns to the British pattern in terms of, I can't remember exactly what's the word because clearly my Swedish and Finnish are not particularly advanced as to say they are. They are probably, no, but it's very interesting to see the same thing happening in different places. What's really interesting is also in places that have, for example, a bilingual community or trilingual community, which is something you find in, um, in certain valets on the Alps between Italy and Austria or Italy.

Giuseppe 40:19 In Switzerland, there are valleys where there's a romance community. So they ha they will have roads with Italian, German and Romansh name. And all this is fascinating because it can give an insight of how, uh, different communities in maybe refer to those streets because the streets normally will have to say name translated, but sometimes they won't. So yeah, it's absolutely interesting to see, um, the different cultural aspects of this. And once again, the, the reason why I've released that code is one because I like to advance the data analysis in a geographical context especially. And one thing that I think is possible with that code is basically to just apply the coloring to any feature. And once again, open street map, uh, has a very rich, uh, layer of data, uh, that can be used for, for that coloring. And of course the other aspect of all this is that that data can be linked to other open data sources, which is one of the important aspects of open data. Uh, and therefore, you know, the coloring would basically take any, any direction. There were people in Amsterdam who did something similar using the age of the buildings because there is a full cadastral dataset would stop information and that's absolutely brilliant.

Steven 41:40 Yup. So you're now selling high quality prints online from, from some of these city maps I gather. So maybe you could give us,

Giuseppe 41:49 Well, once again, that'd be the make me rich. So open data doesn't make people rich. I can't confirm that, but I asked, sold a few, uh, everything is, is a bit quiet now because Royal made deliveries are not particularly, um, quick at the time of growing the virus. They, they have a few, uh, serious issues. But yeah, it was interesting to me to see the full life cycle of having an idea using data to implement it and then produce a physical product out of it. I think that's been absolutely brilliant.

Steven 42:21 Great. And we'll put the link to where those maps are in the episode notes at the bottom. So, Giuseppe, my final question for you, it's the question we ask all about guests on the gym or podcast. What were your, sorry, you've been a regular at GMR I think right from the beginning. Certainly. I met you at one of the very earliest year mops. What have been your favorite moments? Give me a couple.

Giuseppe 42:47 So I have a few. Um, I said I did a talk at the gym all about something called the open data dilution, which at the time I remember shocked a few people, like, you know, like, Oh, everyone thought I was this, uh, open data fanboy, which clearly am, but you know, I like to do that talking, which I was seeing things from a different perspective. But when I gave my talk, there was a going for more than survey called Chris Western. So Chris Weston, who did this fantastic talk about mapping Mars. To me, that was a great moment because that's where I realized that, you know, you can map pretty much everything. Um, you know, once again, there is a bit about the geeky data-driven aspect of producing the knots alongside a, an aesthetic quality of those maps. So that was probably my favorite talk ever.

Giuseppe 43:37 Uh, at GMO. There are other two moments I'd like to mention, uh, mostly for their sort of emotional attachment. So my first job was actually the second germ of ever, uh, which I think, or maybe, I can't remember if that was the first one I attended, but definitely one of the first in which a certain Gary Gaye spoke about who plays maker. And once again, Oh, fantastic stuff about, you know, location and data, uh, on the web at the time. You know, I think this was probably 2009 or 2010 so very, quite a long time ago. And yeah, I mean then, I mean, now I'm friends with Gary and it's great that, you know, I think the thing about Jamal has been the community aspect. I mean, now I, I've developed a few friendships off of that, so I really enjoyed it. Uh, one other moment that I'd like to mention, which I always like to mention is the fact that city mapper introduced at geomob at the very beginning. And I do remember certain Steven Feldman saying, but what's the business model of this? How will you make money? And I sort of think problems.

Steven 44:44 Yeah, they've had tens of millions of pounds worth of investment. But I'm not certain that they've yet found the profit point, but who knows. Maybe they will do just that. It's really been a pleasure talking to you. If people want to get in touch with you, how should they get in touch with you?

Giuseppe 45:02 Oh, many ways. So I mean verbally, I'm one of the few people in my name, so if you Google my name would probably find me. I'm on Twitter. I also have a weekly newsletter which has been going on for now eight years. It was actually the anniversary yesterday. My, uh, so I basically have this weekly newsletter with things about data maps, data visualization

Steven 45:22 And I can recommend it to everybody.

Giuseppe 45:25 Thank you. And yeah, I mean otherwise I'll, as soon as we are allowed back into, um, uh, full, uh, outside activities, uh, probably a Geomob would be the best way to meet you.

Steven 45:37 Great. Giuseppe. Thank you very much indeed. It's been a pleasure talking to you today. Thank you very much. Speak soon.

Ed 45:48 Thanks everyone for joining us today and listening to the GMO podcast. Hopefully you've enjoyed the discussion. Please don't hesitate if you have any feedback for us or any suggestions for topics that we should cover in the future. You can get the show notes over on the website, which is at -inaudible- dot com while you're there, if you're not yet on the mailing list, please do get on the mailing list where we once a month send out an email announcing future events, summarizing past events and just generally sharing events that you may find of interest. You can also of course follow us on Twitter where our handle is geomob. You can follow Steven at @StevenFeldman. You can follow me @freyfogle. You can check out mappery dot org and of course if you need any geocoding, please check out my service, which is opencagedata.com we look forward to you joining us again at a future episode or end of course seeing you at a future Geomob event. Hope to see you there soon. Bye.